Final Years, Freedom on a Chain

On August 2, 1857, Taras Shevchenko sailed for three days by fishing boat from Novopetrovsk Fortress to Astrakhan. From there he took a steamboat up the Volga to Nizhny Novgorod.

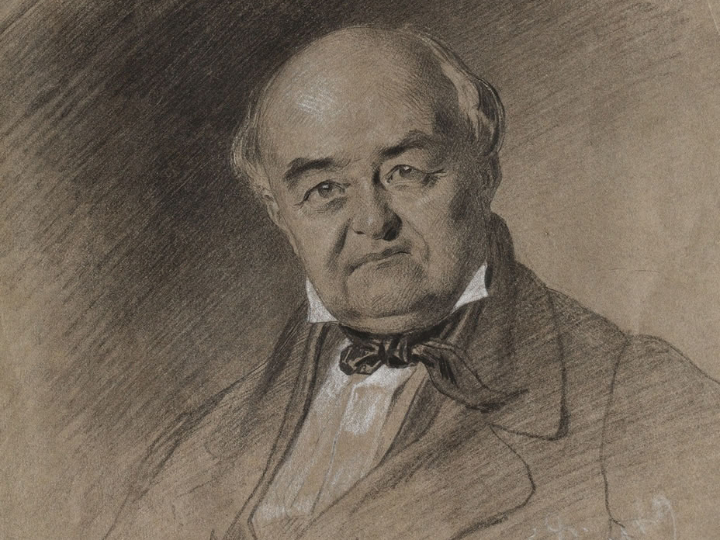

Informed upon arrival that he was forbidden entrance to the capital, Shevchenko remained in Nizhny Novgorod for about six months. "Now I am free... as free as a dog on a chain", he wrote from Nizhny Novgorod to his friend, the famous Russian actor, Mikhail Shchepkin. During his stay, he produced many portraits and drawings.

The poet’s release allowed him to take up his pen, once more. He began by rereading, correcting, and rewriting his earlier works. Simultaneously, he began work on a new poem, The Neophytes, the setting of which was the ancient Roman Empire, a metaphor for the tsarist empire, and the emperor Nero standing in for Nicholas I.

The reader readily saw through the camouflage and understood that Nero was Nicholas I, the patricians were the landowners and upper classes, the plebeians were the people, and the Neophytes were the revolutionaries, champions of the people's freedom.

In March 1858, Shevchenko finally received permission to enter the capital of the Russian Empire. On his way to St. Petersburg he stopped in Moscow to visit with Shchepkin and other friends.

There, he became aware of an intensifying movement led by a new revolutionary-democratic group which was endeavouring to emancipate the working people and bring down the autocracy. He hastened to St. Petersburg, although the freedom that awaited him there was but a phantom, since he would be under constant police surveillance.

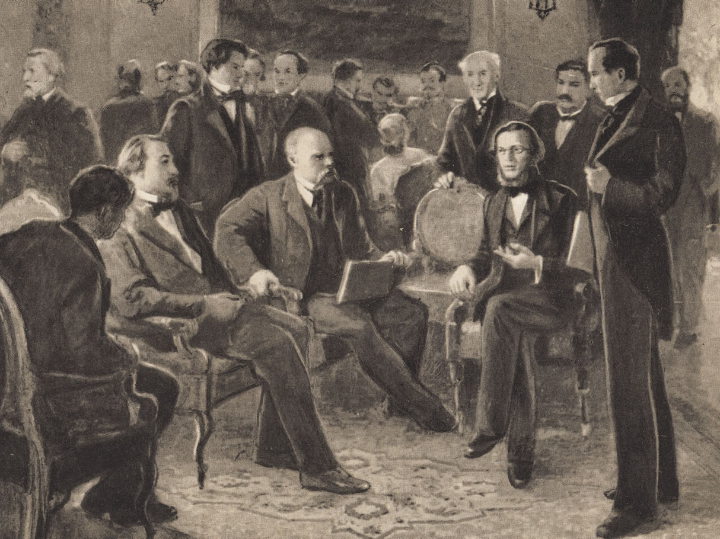

In the spring of 1858, when Shevchenko arrived in St. Petersburg, he was welcomed enthusiastically by the foremost intellectuals who generously opened their literary salons to him. He became closely associated with Chernyshevsky, Dobrolyubov and other writers grouped around Sovremennik, the most progressive journal of that time, and for his revolutionary ardor was held in high esteem by them.

Reaching a higher level of maturity during this period, Shevchenko's political poems became especially poignant. One of his contemporaries wrote:"Shevchenko's accusations have become unrestrained; he strikes, and he smashes; he is all afire with a frenzied, all-consuming flame".

He predicted that the day was near when "they'll lead the tsar to execution," then "there'll be no foes, no evildoers, there will be sons, there will be mothers, and there'll be people on the earth."

Not only did the poet participate in the revolutionary movement of the 1860s, but he also exerted a powerful influence on the development of progressive thought in the Russian Empire. It is no wonder that Chernyshevsky considered Shevchenko an "incontestable authority" on the peasant question, an issue that was of special concern to the revolutionary democrats.

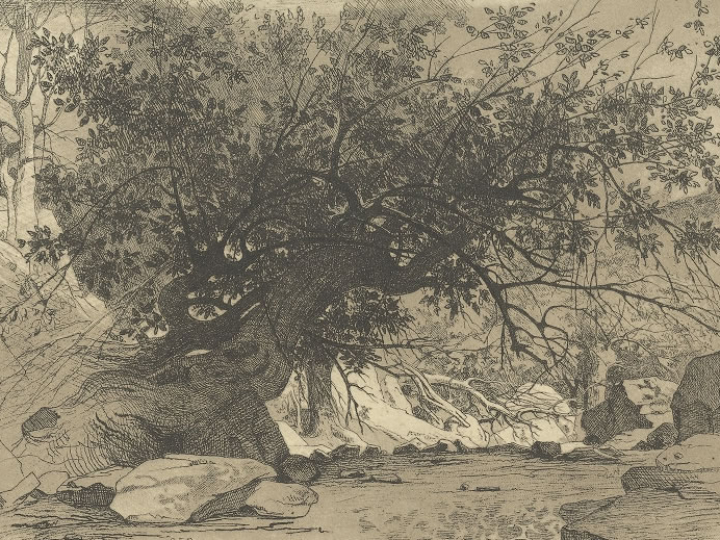

In May 1859, Shevchenko received permission to go to Ukraine where he intended to buy a plot of land near the village of Pekariv. There he planned to build a house in which he would settle for the remainder of his life. While in Ukraine, he visited his childhood haunts and saw his relatives, and observed the same life of poverty and slavery, the same struggle for a crust of bread as before. There, too, he was under constant police surveillance. Gendarmes and spies eavesdropped on his conversations, and in July he was arrested on a charge of blasphemy.

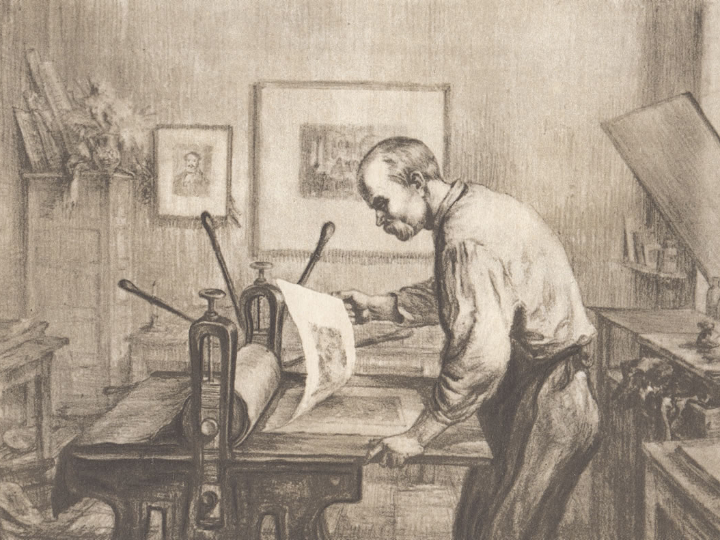

Barred from living in Ukraine, on September 7, 1859, he returned to St. Petersburg where he took up residence in the attic of the Academy of Arts. There he busied himself with engraving, believing it to be a marvellous means for the propagation of art.

Shevchenko achieved significant success in etching and engraving, and on September 2, 1860, The Council of the Academy of Arts granted him the title of Academician of Engraving.

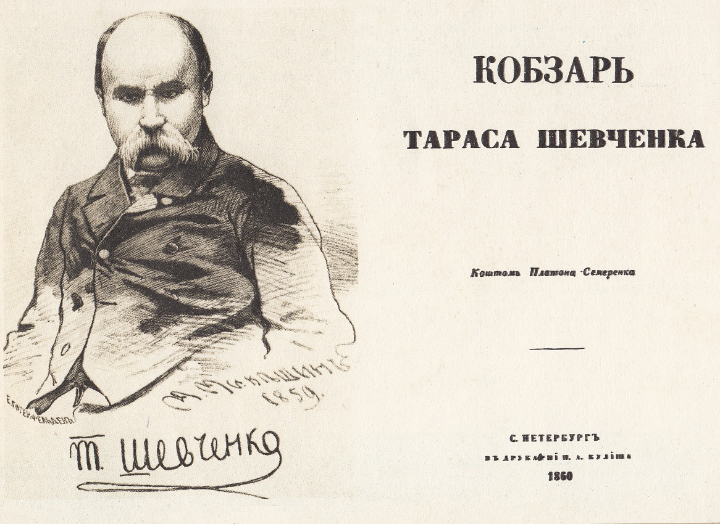

Some of his poems, banned in the Russian Empire, were printed in Leipzig, Germany, in 1859. At the beginning of 1860, the third edition of Kobzar, although highly censored, was published by the Panteleimon Kulish Publishing House in St. Petersburg. In January 1861, to promote public education, Shevchenko compiled and published, at his own cost, a Bukvar (Primer) and provided it free to Sunday schools.

It would be incorrect to assume that Shevchenko limited himself solely to themes and subjects from the life of the peasantry. His broad knowledge of world culture enabled him to turn to any historical epoch.

Describing the bloody struggle of the Haidamaky, for instance, the poet recalled the St. Bartholomew's night massacre; in telling about the Neophytes, he drew an analogy between them and the Decembrists. Shevchenko often turned to biblical themes, especially to the psalms of the old Hebrew prophets, from which he borrowed both themes and epigraphs. He found much genuine poetry both in the psalms and in the legends of the Gospel. All this provided him with material that affirmed the principles of beauty, justice and love of humankind.

From his early years, he was sensitive to oppression and detested the landed gentry who wielded power over the peasantry. Regardless, in the poem To the Dead and Living... (1845) the poet still entertained the possibility... he could yet appeal to the conscience of the Ukrainian gentry:

I pray you, brothers of mine, embrace

Your smallest brother too...

But in time, belief in reconciliation gave way to irrepressible anger and passionate hatred of "the tsar and princelings," gentry, priests and the stooges of the Tsar. The lyrical poems The Dream and The Caucasus, which evoked the wrath of Nicholas I and his lackeys, were written prior to exile and were clearly anti-tsarist in sentiment. Gradually, Shevchenko's evolving revolutionary views were tempered in exile and became fully defined after his release.

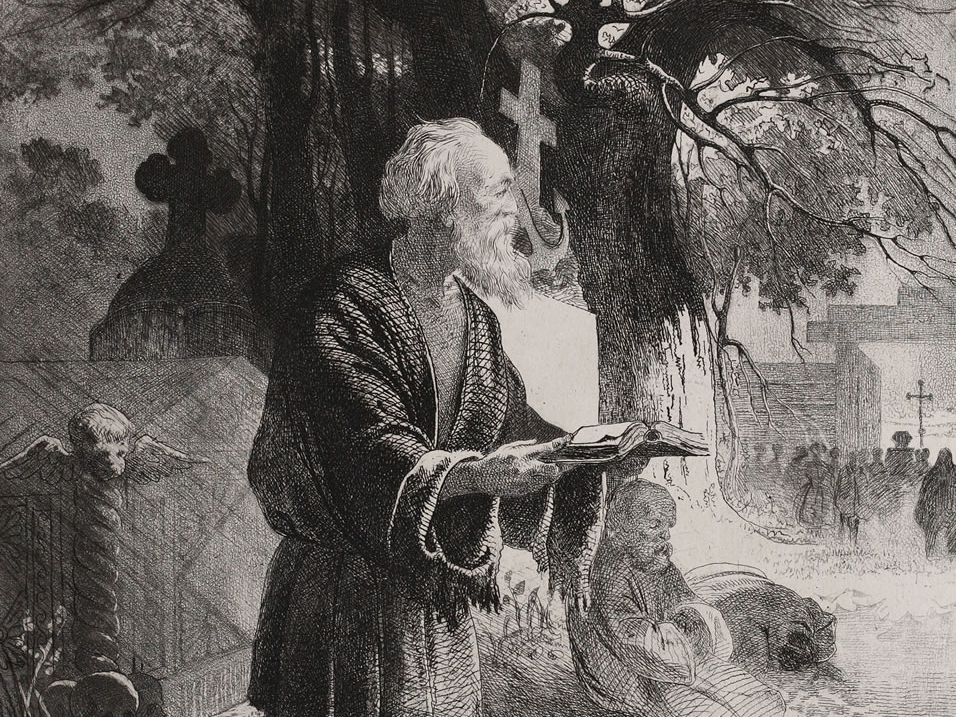

Exhausted, weakened and severely ill from the ordeals he had suffered in exile, in prisons and in Ukraine, Shevchenko passed away in St. Petersburg on the morning of March 10, 1861.

The poet was first buried at the Smolensk Cemetery in St. Petersburg. Fulfilling his wish to be buried in Ukraine, his friends transported his body by train, and then by horse-drawn carriage to his native land, arriving in Kyiv on May 18. On May 20 his remains travelled by steamship to Kaniv, Shevchenko’s final resting place by the Dnipro river.